Delirium, the final frontier

Have you ever been so confused that you are simultaneously certain of your senses and losing your mind?

Maybe you had Covid-19 and thought you were about to cross to the other side.

Maybe one night, you were running a fever, and that veil between imagination and reality slowly faded away until you fell into a spiral of very uncomfortable feelings.

Or maybe you had been working so much and sleeping so little that you would gladly let yourself go into a light slumber right while you are performing.

Don’t worry. No need to be shy. I have been there, too. Floating in the unknown of the human mind.

Delirium is a state of mental confusion that comes on very suddenly and lasts hours to days.

It doesn’t sound like a very alien issue, does it? According to the American Delirium Society, more than 7 million hospitalized Americans suffer from delirium each year. I often wonder how many people go through it in the privacy of their homes and don’t tell a soul. It must be so easy to go unnoticed in a dysfunctional family. Look, auntie Mildred is talking nonsense again… Let’s ignore her for a few days.

Delirium is a psychiatric syndrome known as an acute confusional state, a decline in our mental function over a short period of time. It’s as though the difference between delirium and psychosis is the amount of patience available to the witness. If the witness of such a mental state is willing to make an effort, the victim has a chance of avoiding a hideous label. If whoever is watching the affected contributes to the instability, for instance with gaslighting, then the victim has a lot more lottery tickets to go down the rabbit hole. But, since we lack much evidence to fully describe any of those experiences, I will leave that statement as a personal wild assumption that I needed to get off my chest.

Anyway… What we know for sure is the financial impact of delirium. According to a 2008 study done on the healthcare cost associated with delirium, the national burden of delirium on the healthcare system goes as high as $152 billion each year. If you ask Dr Aaron Pinkhasov from NYU Winthrop Hospital, he will tell you that it can get up to $164 billion a year. And now that Covid has sent a good chunk of the population through intensive care, I reckon that amount has grown even higher.

But $$$ isn’t the greatest consequence of all. Delirium has been proven to have long-term effects on the human mind, as E Wesley Ely often explains in his public lectures.

Patients with delirium have longer hospital stays and lower 6-month survival than do patients without delirium, and preliminary research suggests that delirium may be associated with cognitive impairment that persists months to years after discharge.

This negative outcome often has the looks of depression or PTSD between other manifestations, and it is known as post-ICU syndrome. It seems that the intensive care experience is highly traumatizing, which in a way, explains why the mind enters such a state as delirium.

Unfortunately, the list of risk factors is as long as a Egyptian scroll.

This is a link to the Critical Illness, Brain Dysfunction, and Survivorship (CIBS) Center. It is an organization focused on gathering and digesting knowledge in order to improve models of care for people affected by critical illness, especially delirium.

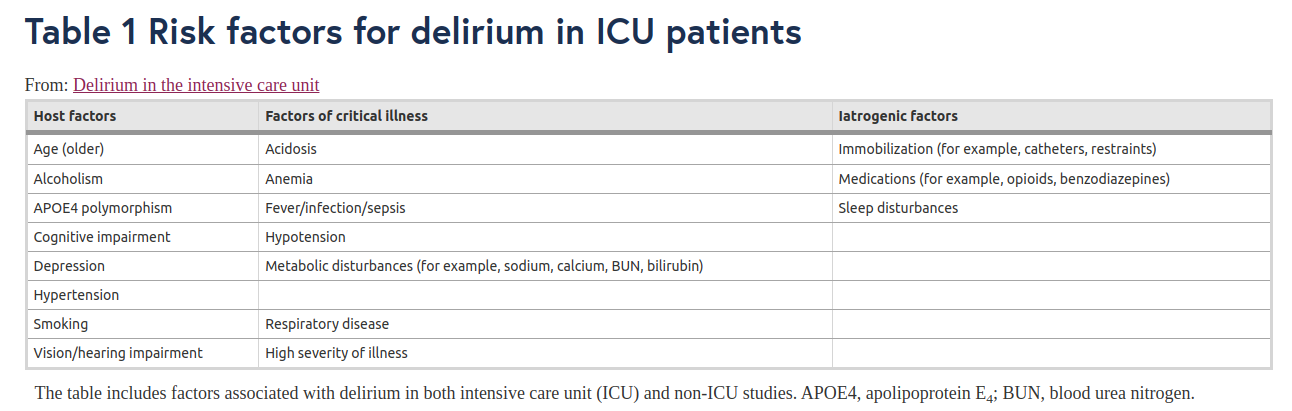

The following table shows the most common risk factors for delirium. Some of them are intrinsic to the patient, as is a visual or hearing impairment. Some others are factors related to the illness they are confronting, for example, a respiratory disease. But here is an interesting group: Iatrogenic factors. Those are aspects of the treatment that produce damage even though they were meant to help in the first place. In that box are immobilization, medication and sleep disturbances.

Sorry about the tiny picture, here is a link to a better display

If you’ve ever been in an ICU, you will know that it is a very bright and noisy environment where heavy drugs are dealt faster than in Ibiza. We may see it as a low price to pay when it comes to helping people, and it is a fair approach to it, given that without them, many people would lose their lives. But what life are we talking about?

Some patients diagnosed with post-ICU syndrome have to leave their jobs and even forego a pleasant hobby due to the severe life-changing consequences of delirium. This is not one unlucky case, these are millions of people. Shouldn’t we at least try to go deeper into those risk factors that we can control?

There is no determined way to manage delirium. In most cases, professionals fall back into antipsychotic medication and physical restrain. This is how it is been done, and they don’t have time or energy to go looking around for alternatives that would make their job even more difficult.

However, evidence shows that benzodiazepines and antipsychotics do not reduce the duration of delirium, they might control agitation and hallucinations, but they don’t improve the outcome of the patient. In this paper about Haloperidol and Ziprasidone for Treatment of Delirium in Critical Illness researchers found that the widely known haloperidol doesn’t seem to significantly alter the duration of delirium compared to a placebo.

Then what? Are we right where it all started 30 or 40 years ago?

Not really. Wes Ely leading the medical community, has developed a patient-focused care method called the ABCDEF bundle in which mobilization, reduction of medication use and close delirium monitoring have an important role.

As a medical community, we now have published data on over 25,000 patients in ICUs all over North America that there is a dose-response relationship between higher compliance with the ABCEDF bundle and higher survival, shorter time on mechanical ventilation, earlier discharge from the ICU and hospital, fewer bounce backs to the ICU, less delirium and coma, less use of restraints, lower cost of care, and lower rates of discharge to nursing homes and rehabilitation facilities.

Because post-ICU syndrome affects not only the patient but the family, too, efforts have recently been put towards interviewing and learning about their experience and perspective. The results of this Australian study prompt the medical community to pay attention to the environment as it appears to be the main “controllable” cause of sleep deprivation, a great contributor to the development of delirium.

Participants described the intensive care as a noisy, bright, confronting and scary environment that prevented sleep and was suboptimal for recovery. Bedspaces were described as small and cluttered, with limited access to natural light or cognitive stimulation. The limited ability to personalise the environment and maintain connections with family and the outside world was considered especially problematic.

Not surprisingly, when medical, allied health and nursing clinicians are asked about it, they show a very similar perspective. Professionals seem to be frustrated with the impossibility of providing comfort to patients and families. When I was a student nurse, I spent a few months in a critical area, and I remember going back home and listening to alarms going off in my head as if I was still in the hospital, unable to turn them off. I cannot imagine how torturous it must be for those patients who find no possible rest from the constant bleep bleep bleep that surrounds them. On top of that, you can add the pain and emotional baggage of a critical illness, though these can be palliated, they are not avoidable.

Participants noted that the bland, sterile environment, devoid of natural light and views of the outside world, negatively affected both staff and patients’ mood and motivation.

The intensive care environment is unconventional, but it doesn’t have to be so hostile. Think about how many technological companies modify their workspace to accommodate workers with special needs. These changes allow neurodivergent people to not only hold a job (which is already very challenging in the regular world) but to excel at what they are doing. If we take this example to the hospital, it is easy to understand the need to redesign the intensive care bedspace. An ICU room must be built with the needs of the people using them in mind.

In April 2019, Philips introduced VitalMinds, a new non-pharmacological approach to help reduce delirium in the ICU based on an improved design of the bedspace. This project monitors noise disturbances and manages the patient’s exposure to normal levels of light, which potentially allows better control of natural sleep-wake rhythms for patients.

Source: Philips VitalSky

The preliminary results of a study done by Alawi Luetz show that a modification in the ICU environment is significantly associated with a reduced delirium incidence. But why is this direction of research and development so relevant to mental health in general?

Psychology and psychiatry are fields with very little consensus between their professionals. Science seems to have trouble getting to understand the human brain and, even more, human behaviour. I think we can all agree that more research is needed.

Early this year, the World Health Organization (WHO) informed that the global prevalence of anxiety and depression increased by 25% during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Those are not issues that stay in the past. According to UN News, nearly one billion people worldwide suffer from some form of mental disorder, as stated in the last World Mental Health Report published on 16 June 2022. Numbers are telling us that we are, and sadly have been for a while, suffering a mental health pandemia. Isn’t that reason enough to act on it?

Shouldn’t we take this “invisible virus” as seriously as we did with the corona?

We live in a society that pushes us daily to work hard and to live fast. But humans are no gods. Humans can only do so much. I, that have experimented with the tortures of hallucinations and delusions, urge you all to look at delirium as the end of the rope—that point where our mind finds a wall or an abyss. I don’t know which one, but I think we ought to know where the limits of the human mind are, or else, how are we going to confront this new pandemia of mental illness?

Support the author and get the latest publications subscribing to:

Look at her latest book 📕, En Brandán