A book that makes no sense so it can make sense of life.

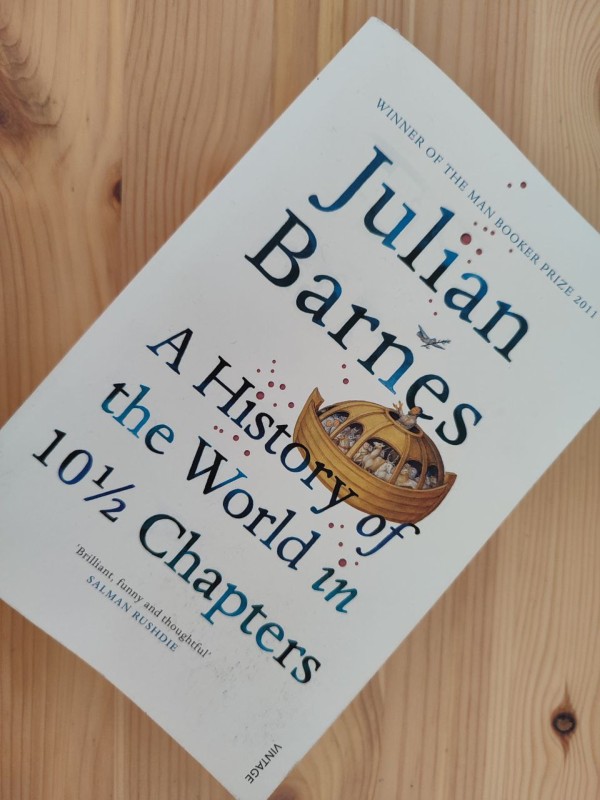

Indeed, it’s not a recent book, but it is still very necessary. You’ve might have heard of it or even read it in 1989. If you haven’t, it doesn’t matter, you can enjoy this piece anyway as I have selected a few passages that you can read along the article.

Here is a summary of the book.

Most readers wonder why Barnes has written a collection of stories that have very little in common, and yet, create a composition in itself thanks to those cues he dropped along the way. Some considered it a boastful moment, the performance of an egomaniac impulse, the showing off of his writing skills. Though there might be some truth in it, I think that was not his major objective.

Of course, he wanted to attract some attention. That is for sure, as it seems to be the flaw and virtue of any writer. But he did not want to catch that attention only to please himself. I believe he had a message to deliver, a message that we humans refuse to hear. A delicate subject that is bigger than any debate.

Barnes spends most pages remodelling history, reinterpreting it or even adding new perspectives to it. At first glimpse, it might seem like a disdain for history, but it is far from it. ly finds it not only fascinating but entertaining. Most disciplines become tedious once you go deep into the matter. However, history offers you plenty of easily digestible stories enjoyable to anyone no matter their knowledge or particular likes.

When the seven of us climbed out of that ram’s horn, we were euphoric. We had survived. We had stowed away, survived and escaped — all without entering into any fishy covenants with either God or Noah. We had done it by ourselves. We felt ennobled as a species. That might strike you as comic, but we did: we felt ennobled. That Voyage taught us a lot of things, you see, and the main thing was this: that man is a very unevolved species compared to the animals. We don’t deny, of course, your cleverness, your considerable potential. But you are, as yet at an early stage of your development. We, for instance, are always ourselves: that is what it means to be evolved. We are what we are, and we know what that is. You don’t expect a cat suddenly to start barking, do you, or a pig to start lowing? But this is what, a manner of speaking, those of us who made the Voyage on the Ark learned to expect from your species. One moment you bark, one moment you mew; one moment you wish to be wild, one moment you wish to be tame. You knew where you were with Noah only in this one respect: that you never knew where you were with him.

—Chapter 1: The stowaway; A History of the World in 10½ Chapters by Julian Barnes (1989)

Barnes shows history as the weapon it is. A weapon used to justify cruelty or any other impulses men can have. And that is why it matters who is telling the story (history) because whether someone has a clear agenda or not, they are going to have a subconscious one.

His view of history can also apply to the present, and especially, to the communication field. We are experiencing political polarization, wars that don’t seem to find an end because whoever is giving orders is not willing to change their perspectives, not even an inch.

“That you never knew where you were with him” is the unsettling feeling millions of people have nowadays. We looked at the future and we see “Noahs” telling us stories about what will be of us, but all we know for certain is that we cannot trust them.

A close and recent example of England (Barnes’ home country) is Brexit; millions of people voted for an imaginary future based on a history that never happened. But politicians know very well how little reality matters, when it comes to convincing people, all that matters is emotions. And stories are definitely the best way to get there.

Often enough, reviews have pointed out the interest of Julian Barnes in history and the preoccupation with love in his work. However, I would include truth in the cocktail if we really want to dig deeper into the meaning of this work of art.

You aren’t too good with the truth, either, your species. You keep forgetting things, or you pretend to. The loss of Varaldi and his ark — does anyone speak of that? I can see there might be a positive side to this wilful averting of the eye: ignoring the bad things makes it easier for you to carry on. But ignoring the bad things makes you end up believing that bad things never happen. You are always surprised by them. It surprises you that guns kill, that money corrupts, that snow falls in winter. Such naivety can be charming; alas, it can also be perilous.

—Chapter 1: The stowaway; A History of the World in 10½ Chapters by Julian Barnes (1989)

If we think of him just as a writer, we can infer a love for stories, which is how he sees history and possibly why he’s chosen to bring historical events into his narrative. He doesn’t give much importance to the details and doesn’t care if they are believable or not, for that he’s chosen to tell his first chapter from the perspective of a woodworm. Instead, he worries about the implications of the moral. He doesn’t do this by proving a new one, nor he pretends to lay out alternative teaching. He simply states the little reliability of any story, and therefore, of history.

I wouldn’t be surprised if he is not entirely confident about his ideas and so he rather leaves the conclusions to the readers, perhaps he even enjoys listening to whatever people have reflected about his hieroglyphics.

This lack of guidance, this refusal to clearly say what he wants you to think, I found it to be a sign of modesty. Personally, I am tired of reading texts that point me in a direction and threaten me if I dare to look around in search of any other options. You only have to read the comments section of any current topics to see that considering other possibilities is pretty much synonymous with treason. Not national treason per se, but personal treason for sure.

Love and truth, that’s the vital connection, love and truth. Have you ever told so much truth as when you were first in love? Have you ever seen the world so clearly? Love makes us see the truth, makes it our duty to tell the truth. Lying in bed: listen to undertow of working in that phrase. Lying in bed, we tell the truth: it sounds like a paradoxical sentence from a first-year philosophy primer. But it’s more (and less) than that: a description of moral duty. Don’t roll that eyeball, give a flattering groan, fake that orgasm. Tell the truth with your body even if — especially if — that truth is not melodramatic. Bed is one of the prime places where you can lie without getting caught, where you can holler and grunt in the dark and later boast about your “performance”. Sex isn’t acting (however much we admire our own script); sex is about truth. How you cuddle in the dark governs how you see the history of the world. It’s as simple as that.

—Chapter 8½: Parenthesis; A History of the World in 10½ Chapters by Julian Barnes (1989)

If you ask me, that half chapter called Parenthesis is why Julian Barnes has written the other ten. He needed elaborate examples that would open up people’s minds and prepare them for what he had to say. Again, he didn’t want to give a clear conclusion about love, but you can see he feels much stronger about this subject than others. Though we all do, one way or another.

Julian Barnes compares history and love, and he does that by redefining truth.

We all have our own history, we all tell our preferable stories, and we all love someone despite our worlds can never be met. Truth doesn’t exist which means putting too much emotion into it won’t get us closer to any existential answer or any kind of success. However, unconditional love, that love that acknowledges our differences and doesn’t try to change the other to meet our particular point of view is what will allow us to remain together as a society. That we can learn in our relationships, and hopefully transfer to our society.

We can only hope our loved ones will gravitate towards a truth that will allow us all to be free, but we cannot do much about it behalf telling them our favourite stories. Some will use this opportunity to manipulate, and this way they will stain the name of love for many; and some others will use it to open windows to those who sit behind the high walls of indoctrination.

Now more than ever, being aware of the feebleness of history is crucial. We cannot trust those who tell us stories out of their own emotional baggage while we cannot forget the emotional baggage that most societies carry which must be addressed in other to heal. Extremely complicated subject for only 309 pages. And so the question remains.

What is love?

What is truth?

And what history should we listen to?

Support the author and get the latest publications subscribing to:

Look at her latest book 📕, En Brandán